The ‘Great White Hopes’ Aimed To Rescue The White Man From A Black Boxing Champion

In 1908, in the height of the Jim Crow era, boxer Jack Johnson became the first Black World Heavyweight Boxing Champion.

Soon after, America’s “Great White Hopes,” a term coined at the time by writer Jack London, were urged on by calls that “the White Man must be rescued.”

In other words, for all of North America, it was unacceptable that a Black man was the best boxer in the world.

The first “white hope” was former World Heavyweight champion Jim J. Jeffries. Jeffries left boxing in 1905 after stating he would retire “when there are no white men left to fight.”

He retired undefeated, but had never before beaten Jack Johnson.

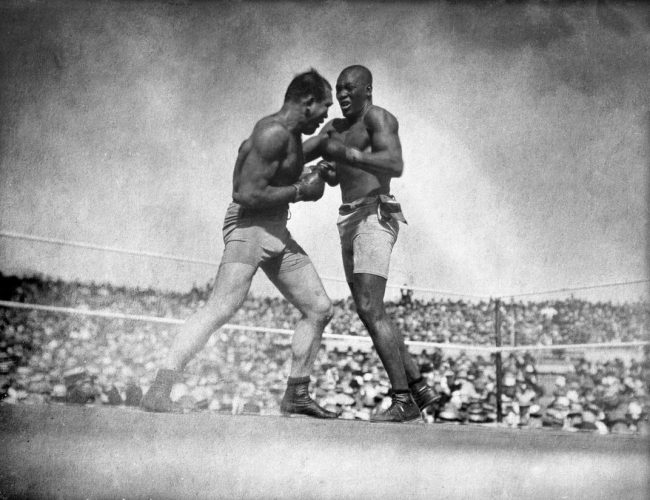

This information precipitated what people referred to as the ‘fight of the century’ in 1910 when Jeffries came out of retirement saying “I am going into this fight for the sole purpose of proving that a white man is better than a Negro.”

Johnson, who was the son of slaves, replied by saying “May the best man win.”

After 15 rounds, Jim J Jeffries’ corner threw in the towel in what many described as the most lopsided championship bout in history. Jeffries had failed to achieve his goal to “reclaim the heavyweight championship for the white race.”

Rather, fellow boxer John J. Sullivan proclaimed “The fight of the century is over and a black man is the undisputed champion of the world.”

This proclamation, and the result of the fight, sparked Nationwide race riots fuelled by angry white populations.

Despite the win, the fight related to race was just beginning.

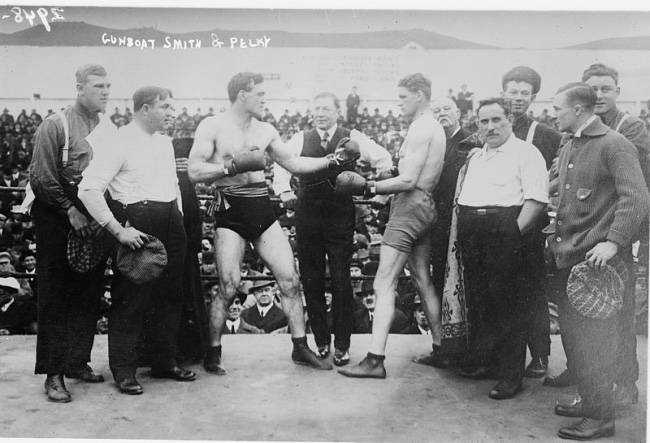

Locally, one of the fighters dubbed a “great white hope” who needed to defeat Jack Johnson, was Pain Court’s Arthur Pelkey.

In 1911, an elimination tournament of ‘white hopes’ was held in New York to find the best candidate to dethrone Johnson. The winner of this event, who was titled the “World White Heavyweight champion” was Al Palzar.

Two years later, Chatham-Kent’s Arthur Pelkey became the World White Heavyweight champion in a tragic fight, where he defeated Luther McCarty, who was pronounced dead only 8 minutes after the fight ended.

Pelkey was charged with manslaughter, a charge he was later exonerated of, but lost his next 10 fights, and never fought Johnson.

Johnson had his own legal struggles, being charged and convicted under a racially motivated interpretation of the Mann Act, for what people saw as his immoral relationships with white women. The judge who convicted him was Kenesaw Mountain Landis, who later became the first commissioner of professional baseball, and was the final commission to uphold the colour line, barring Black players from the Major Leagues. Jackie Robinson made his Major League debut in 1947, three years after Landis’ death.

At the time in sports, there were few athletes more polarizing in sport. As historian David Wiggins wrote, “Johnson drew the wrath of segments of both the African American and white communities because of his unwillingness to assume a subservient position and play the role of the grateful black.”

His story has been told multiple times, including in the 2004 PBS documentary titled “Unforgivable Blackness.”

Issues with race and boxing however, far precede the era of “great white hopes,” and issues related to race exited long after this era as well.

In the 1700s, slave owners would pit slave against slave in bare knuckle boxing for entertainment, wagering on the outcome, while watching slaves beat each other to near death.

Such fights were commonplace in antebellum Alabama, and across the South. One such famed fighter was Tom Molineaux, who was born into slavery in Virginia in 1784. Molineaux obtained his freedom from slavery after winning the son of the plantation owner $100,000 in a fight against another slave. Following this, Molineaux was said to be crowned the “Champion of America” for his subsequent fights in New York.

In the 1960s, Muhammad Ali was the face of boxing, and became fixed within social issues, and the movement for racial justice.

One of the greatest athletes of the past century, Ali was an advocate for racial integration, and famously refused the Vietnam draft.

For Ali, who defeated every top boxer of the time, and faced racial prejudice of his own, the sight of two Black fighters entering the ring against each other sparked visions of slavery and continued oppression.

“We’re just like two slaves in that ring. The masters get two of us big old black slaves and let us fight it out while they bet, “My slave can whup your slave.” That’s what I see when I see two black people fighting,” Ali is quoted.

In fact, it was the day after Ali claimed the heavyweight title in 1964, defeating Sonny Liston, that he renounced his “slave name,” Cassius Clay, joined Islam, and became Muhammed Ali.

The history of boxing, as with all sport, is woven inseparably with racism, oppression, and questions of social responsibility.

The era of the “Great White Hopes” came to an end on April 15, 1915, when Jess Willard defeated Jack Johnson to claim the Heavyweight title.

The White Hope era came to an end on April 5, 1915, with Jess Willard’s win over Jack Johnson for the Heavyweight Championship of the World. Following this fight, few Black fighters got the chance to fight for a heavyweight title for the next 20 years, until Joe Louis was crowned World Heavyweight champion in 1937.

In the modern world, championship boxers are showered in celebrity and wealth. Throughout history however, the impact of the sport on Black athletes, leaves a disproportionate, and negative legacy.

Similar to the current issue of race norming in NFL concussion settlements, boxing has left Black fighters at a disadvantage following their careers.

As a recent study clearly stated when looking at heavyweight champions, “Compared with white boxers, non-white boxers tend to die younger with excess neurological and accidental deaths, and they have lower social positions in later life.”

The “Great White Hope” era will undoubtedly go down as one of the most overt racist periods of sporting history. It directly pitted athletes against each other in a race war, with one side, the white, deemed as deserving and good, and the other side, the Black, deemed as a threat to be defeated.

By Ian Kennedy

Line Change is an article series produced by CKSN.ca through the contributions and consultation of various authors and academics, looking at social issues in sport. The series, which aims to open discussion with sports fans, will focus on issues of inequality, and serve as a portion of our anti-oppression education and reporting. Line Change will look at issues related to racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, gender inequality, socioeconomic divides, and much more, as they relate to sport and athletics.